Growing Student Success

One Seed at a TimeTaylor Pruitt is an agricultural business and hospitality innovation double major. She’s a busy sophomore involved in her sorority, taking in study groups and coffee breaks and Arkansas football games. But between classes, instead of heading back to her room or chatting with friends, Pruitt heads over to a shipping container where she spends around 20 hours doing one thing – farming lettuce.

Since August 2016, Chartwells has been growing lettuce in a shipping-container-turned-sustainable-farm called the Leafy Green Machine. The farm comes from an environmentally conscious, sustainability-minded company based out of Boston, Massachusetts, called Freight Farms.

Protected from temperature changes and other environmental disturbances, the refurbished shipping freight is a fully functioning hydroponic farm that uses a vertical growing system. With approximately 260 hanging towers, over 3,000 heads of lettuce are growing in the Freight Farm at any given time.

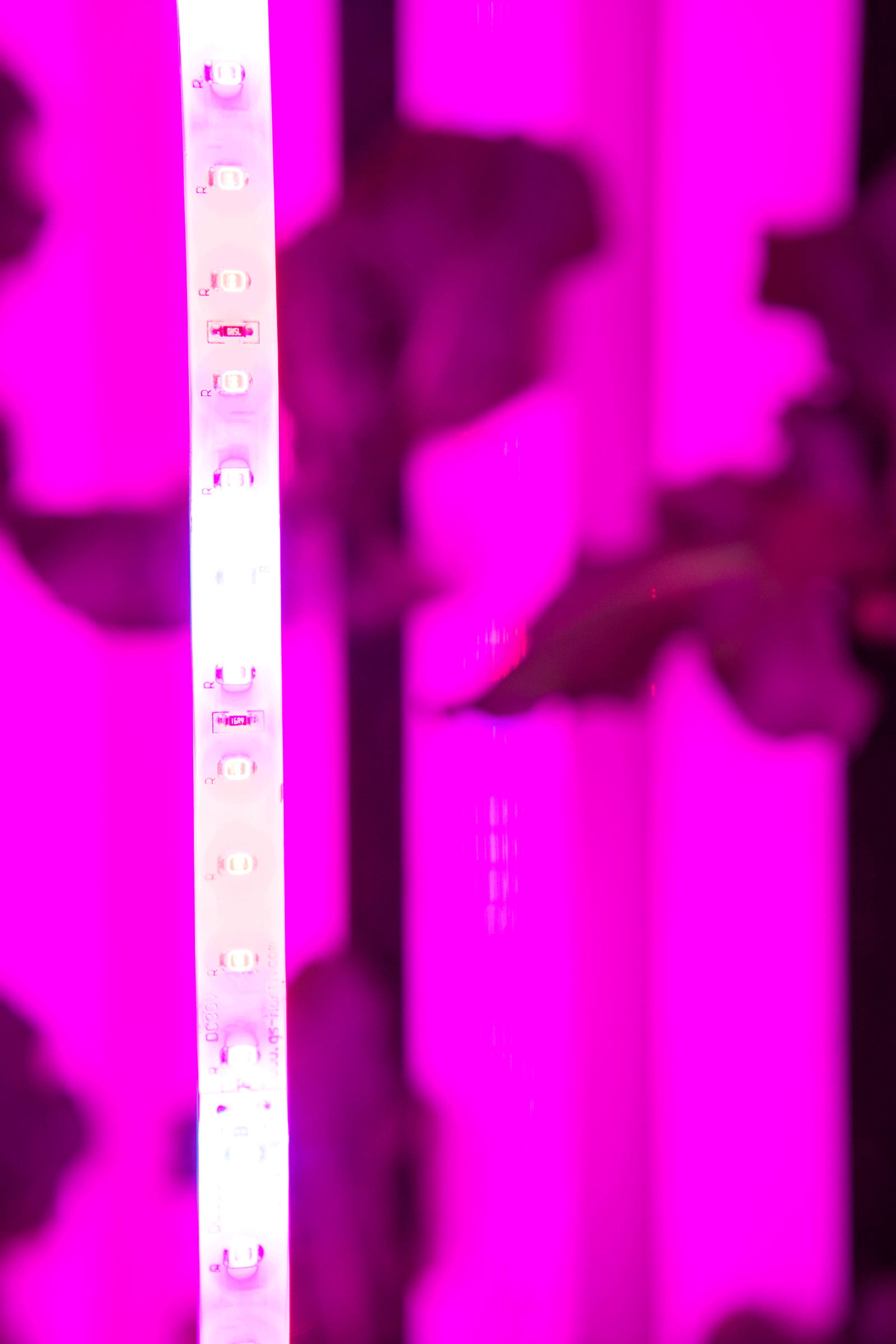

Inside the container, LED light strips provide crops with shades of red and blue – the light spectrums required for photosynthesis. A hydroponic system delivers a nutrient rich water solution directly to roots, using only 10 gallons of water a day. Energy-efficient equipment automatically regulates temperature and humidity in the Freight Farm through a series of sensors and controls.

Overall, the Freight Farm project has the potential to shorten the food supply chain, cut emissions, decrease costs, and overall, significantly reduce the campus’ carbon footprint.

After sliding off her backpack and switching off the LED growing lights for the overhead fluorescents, Pruitt begins her work. She examines the health of the heads of lettuce and replants sprouting seedlings that have moved on from germination. She checks the nutrient levels on the in-house farm monitoring system. If it’s time to harvest a crop of lettuce, she throws her hair back and starts slinging vertical growers around with a speed that can only come with familiarity.

Pruitt, along with Merrisa Jennings, another student worker, and Ashley Meek, nutritionist and staff manager of the Freight Farm project, all work in the farm during the week. They handle weekly harvests, un-racking vertical growers, removing the lettuce head, bagging it, replanting the rack with a new seedling, and repeating.

The entire project is funded by Chartwells Dining Services. Why pour funds and resources into a project like this? Growing student success.

Heads of Lettuce Harvested

# of hours spent in the Freight Farm each week

Number of Student Workers

“Of course we want to be able to reduce waste and shorten the food supply chain on campus – we’re always looking for innovative ways of doing that, but we also want to do is work with students,” Lipson said. “We want to bring them in however we can. I mean, we’re here to serve them. They’re the reason why we come into work everyday.”

Lipson said after securing the funding and space for the Freight Farm, it was time to find a staff.

“And then we met Taylor,” Lipson said. “She was this dynamic, energetic freshman we met at a hospitality fair at 8 a.m. in the morning on a Saturday. That shows some real initiative, especially from a student at that stage of their college career. We instantly knew she would be a great fit for the project.”

Lipson, Pruitt and other Chartwells employees travelled to Boston to train with Freight Farm staff members on how to maintain the farm and be successful hydroponic farmers. The two-day training consisted of technical skills and community development.

Outside of the environmental benefits of the Freight Farm and the delicious, leafy greens it brings to campus dining halls, the hydroponic farm is fostering a deep growth of interest in students for community engagement, food security, and social responsibility.

For Freight Farms the company, the main goal is to spread an awareness of the need for sustainable solutions to food systems and breed a kind of connectedness and engagement with the community on where it’s food comes from.

“We’re not just selling a product, we’re building a community,” Caroline Katsiroubas, director of marketing for Freight Farms said. “If we’re trying to decentralize the food system and put the power back into the hands of the smaller farmers, we have to invest in an infrastructure that will follow them throughout their journey. We want people to join the movement and push it forward.”

Katsiroubas said the company has always been interested in working with institutions of higher learning.

“The coolest thing has been seeing the enthusiasm and almost urgency to get Freight Farms onto college campuses,” Katsiroubas said. “There is such value to having a Freight Farm on campus because its not just the fresh produce – its having students interact with sustainable farming and engaging with locally grown produce. It allows the food to be attached to a larger story of community engagement.”

“I’ve always had an interest in agriculture. I grew up going to my grandfather’s farm and my dad had one too. So I have a real appreciation for the actual cultivation of plants. I take classes where I learn about plants and the science behind it, but working on the Freight Farm is a common ground between my two majors. It brings together agriculture in the way that food is produce and hospitality in the way that food is given to the consumer.”

With the global community concerned about the pervasive global warming, food, and water security issues, teaching students about sustainable food options is vital to building tomorrow’s innovators.

For Pruitt, her job working at the Freight Farm is a creative way to combine both of her interests of agriculture and hospitality.

“I’ve always had an interest in agriculture. I grew up going to my grandfather’s farm and my dad had one too,” Pruitt said. “So I have a real appreciation for the actual cultivation of plants. I take classes where I learn about plants and the science behind it, but working on the Freight Farm is a common ground between my two majors. It brings together agriculture in the way that food is produce and hospitality in the way that food is given to the consumer.”

This past year, Pruitt took an educational trip to India and interacted with food insecurity in a way she never had before.

“Being in India, it helped me get that bigger picture of what is going on in our world and what needs to be worked on,” Pruitt said. “I feel like working in the Freight Farm is me contributing to society and contributing in a way that I can use my knowledge, my information, my resources to contribute and make this world a better place.”

“We can’t live in a world where we have people dying of starvation. People are dying because we can’t figure out a way to provide food soon enough,” Pruitt said. “Working in the Freight Farm, participating in that community and spreading that knowledge, I feel like is one small way for me to make a difference.”

Pruitt said working the in the hydroponic farm day-to-day is giving her a real world connection to what she’s learning in the classroom.

“Actually working in a hydroponic farm makes it so real. That’s why I’ve been so thankful that Chartwells decided to invest in students. Chartwells has invested so much into me, and they want to make sure that students here get involved in things they’re passionate about,” Pruitt said. “Whenever they first told me about the Freight Farm, I was excited to work on the project but I wasn’t super passionate these environmental process or food security. But it’s become such a reality in my life, and it’s made me realize we really need to work more on projects like this and further this project so we can provide for people and help people provide for themselves.”

Not only is Pruitt working to build a more informed and sustainable community at UARK, she is building her resume.

“Professors would love to send kids for professional development and out-of-classroom experiences if they could, but they don’t have the money to do that. Chartwells has been able to hire students, giving me work while I’m in school,” Pruitt said. “I have to work to get myself through school, so I would have been working a normal part-time job. That job would have gotten me through, but it wouldn’t have given me a once in a lifetime opportunity like the Freight Farm project has given me. Other students don’t get to do this everyday. I feel so lucky and blessed that I’m a part of something like this.”

“The degrees that we offer here, whether it be biological engineering, horticulture, agriculture, cultural sciences and environmental sciences – all of these degrees would work really well with working in the Freight Farm. I think it gives them an alternative idea of what they could use their degrees for instead of the conventional go work on a farm or go to food processing centers. Those jobs are important and needed, but this gives them an option they might not have thought about before. It gives them a completely new area of study to look towards.”

In order to take better care of the environment and find a way to feed the hungry, farmers and scientists must get creative. Environmental solutions like the Freight Farm project might be one answer to the complicated issue of food insecurity and environment consciousness farmers and scientists face. Moreover, as the world becomes more urbanized, vertical farming like Freight Farms can be used to help meet the increasing demand for fresh local produce.

Merissa Jennings said working in the Freight Farm brought life to what she’s learning in the classroom and gave it a practical, real-world application.

“I took a class called Sustainable Biosystem Design this past semester. It’s all about making sure whatever you’re doing, whether it be building a bridge or building a power plant, from start to finish it comes from sustainably sourced materials with efficient designs,” Jennings said. “So this is something that touches home because the Freight Farm lives in a cargo container – Freight Farms recycled the container, the nutrients they give us come from reused or recycled materials, and it runs on very little energy and water.”

Jennings, a biological engineering and biochemistry double major, is graduating in May 2018 and heading off into a career that will involve graduate school, but ultimately a career in sustainable community development.

“The Freight Farm project definitely ties into what I’m learning in school, and then what I’ve noticed with all my experiences both here and abroad,” Jennings said. “Food is a huge necessity; I think we all can agree on that. One of the biggest environmental issues that we have is the way we are currently producing our food; it’s really, really damaging to our environment and our water systems. It’s also economically detrimental to us because the more fertilizers we have to keep adding to soil, the more it’s being drained of nutrients. And then because of all the crops we’re putting into the soil that fertilizer is going to start running off, and it has been running off into our water systems, making it more and more expensive for us to clean that water for us to drink it. The cycle for human implications is huge. This project just shows me that this is another way we can lessen our effect on our food crisis.”

Jennings is excited about what her future career in biological engineering and biochemistry and the possibilities ahead.

“I’m really interested in sustainable community development – plant genetics, bacteria genetics, yeast genetics. I want to go into either biofuels or food production or maybe even both, because with plants, you can mess with their genetics and make them better for food and fuel,” Jennings said.

“Let’s say, for example, with crops you can use corn stalks, the part of the plant that’s not edible, and turn that into biofuels. I could use genetics with the plants to make them a better food source. I can change the microbes that will be eating that corn stalk to be converted into biofuels. I can even change the corn stalks genetics so it produces a certain protein or make them more resistant to pesticide if that’s something that’s going to be used on the crops. The possibilities are endless and the impact is so great when you’re dealing with plant genetics.”

Jennings said students with a variety of majors in STEM could benefit from working in the Freight Farm.

“The degrees that we offer here, whether it be biological engineering, horticulture, agriculture, cultural sciences and environmental sciences – all of these degrees would work really well with working in the Freight Farm,” Jennings said. “I think it gives them an alternative idea of what they could use their degrees for instead of the conventional go work on a farm or go to food processing centers. Those jobs are important and needed, but this gives them an option they might not have thought about before. It gives them a completely new area of study to look towards.”

Jennings said she realizes the high-level science behind some of these processes turns students away from learning about agriculture and sustainability, but being able to bring students into the Freight Farm and tell students about it around campus really breaks down the barrier of entry.

“That’s the ‘wow’ factor, because bringing student in here who have no idea what the Freight Farm is, even if the students aren’t already passionate about sustainable food processes, showing them what we’re doing kind of breeds this curiosity and draws them in,” Jennings said. “We’re told to question everything during college and explore ideas we haven’t been exposed to yet, so I think its pretty cool that we’re able to introduce these ideas not just to already passionate, sustainability minded people but to the average student who wouldn’t have any idea about sustainable farming through the shipping container.”

“Not only did we want to give our campus fresh, locally grown produce, we also wanted to make it an educational experience. I feel like you’ve really established a great program for students now and we’re looking forward to continuing that.”

Ashley Meek, the campus dietician for Chartwells at the University of Arkansas and staff member in charge of the Freight Farm project, said the future of the Freight Farm looks like producing even more lettuce, maybe some different herbs as well, and potentially hiring more students and taking on interns.

“Not only did we want to give our campus fresh, locally grown produce, we also wanted to make it an educational experience,” Meek said. “I feel like you’ve really established a great program for students now and we’re looking forward to continuing that.”

The Freight Farm has consistently produced a harvest every week since August 2016. Meek said the consistency is not just because of the innovative engineering of the Freight Farm, but because of the dedication and hard work put in by the student workers.

“Taylor and Merissa’s two unique backgrounds come together so well, and so much of both worlds end up playing a role in our Freight Farm,” Meek said. “They’re the primary operators. They get to run it on a day-to-day basis. They both handle the nitty-gritty work that goes into hydroponic farming.”

Meek said she is proud of what the team has been able to accomplish and what they’ve been able to contribute to the campus food system.

“People want their produce from where they’re living and where they’re working. Being on a large campus where we serve over 10,000 meals, it can be a real challenge trying to source that much local produce,” Meek said. “The Freight Farm is one way we can start attacking that problem.”

The Freight Farm will continue to produce harvests over the summer, seeing new student workers come and put in work on the hydroponic farm, planting new opportunities to grow more student success.